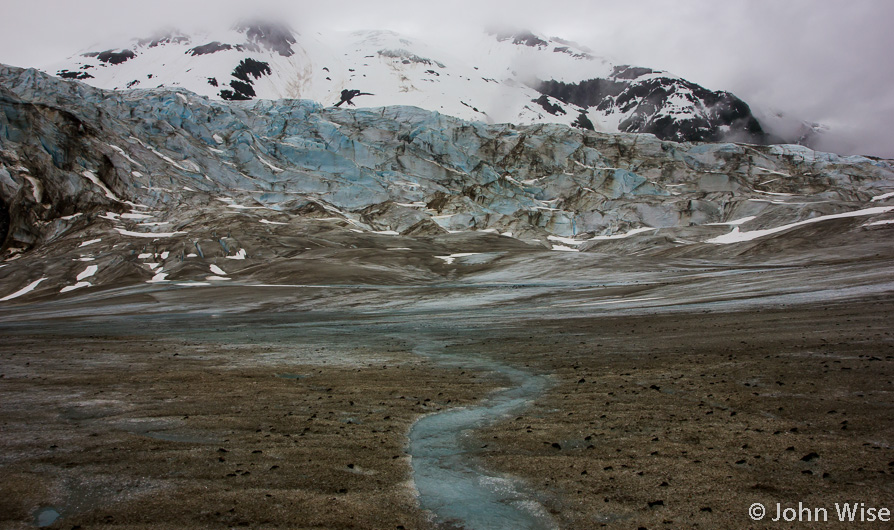

What many of my photos can’t show you is the scale of the environment around us. Everyone knows Alaska is big, but they often don’t realize how big until they have an opportunity to visit. The raft in this photo is about one-quarter of a mile away (402 meters); as you can see, we are dwarfed by our surroundings. We waited around this morning before departing camp, “Maybe the weather will clear?” Nope, it’s overcast and lying down low.

As has been routine during this journey, we need drinking water, and what better place to collect it than from a mountain stream crashing into the Alsek? We pull up, drive-through-like, and while holding onto some tree limbs, our boatman leans out, dipping a 5-gallon canister into the fastest-moving water until it’s full. We let go and drift away, and then the next boatman takes our place, filling his can and so on until we have enough water for the day. I wish I could share with you how amazing it is to drink fresh water that is untreated, -stored, -piped, -filtered, or otherwise touched by mankind. It is cold, fresh, and even a bit daring. How many of us don’t know what freshwater is, aside from it flowing out of a tap in our home? And so when we have this golden opportunity to get our first taste of “free-range” water, there is a moment of apprehension in which we playback the fear-mongering news about how all of our natural water sources are now polluted, are becoming rarer, carry microbes that can make us sick, but here we are taking water from mountain streams every day and living to tell the story. Next time I’m in Alaska, taking a drink from a fast-moving cascade of falling water will be my first indulgence.

Here we are, just seven days away from the 4th of July, with all the ambiance of winter surrounding us. This is deceiving as everything can change around the corner, and it often does. I consider myself lucky to have had this view. Should every day have been sunny, I would have left the Alsek with no idea what the area might look like during the months travelers cannot venture into this area of Alaska. Instead, I will have had a glimpse of those long winters that begin in late September and run through late May – with the added benefit of daylight!

Sure, there is the wondering of what lies hidden above the shroud, intrigue even, but this leaves us with a mystery that only the imagination can fill in. For me, maybe there’s a Yeti just out of sight, probably not, but you can’t see above the clouds to verify it wasn’t there.

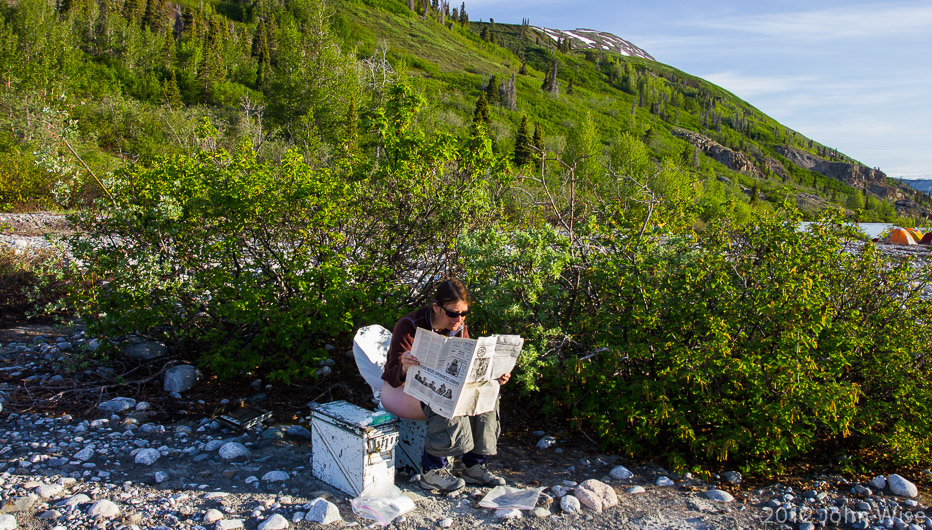

Out of winter and into springtime, or is it now summer? We pulled ashore on a narrow beach to share some lunch. Our landing serves two purposes though, the second being this is a great location for a short hike that would let the boatmen scout the entry into Alsek Lake.

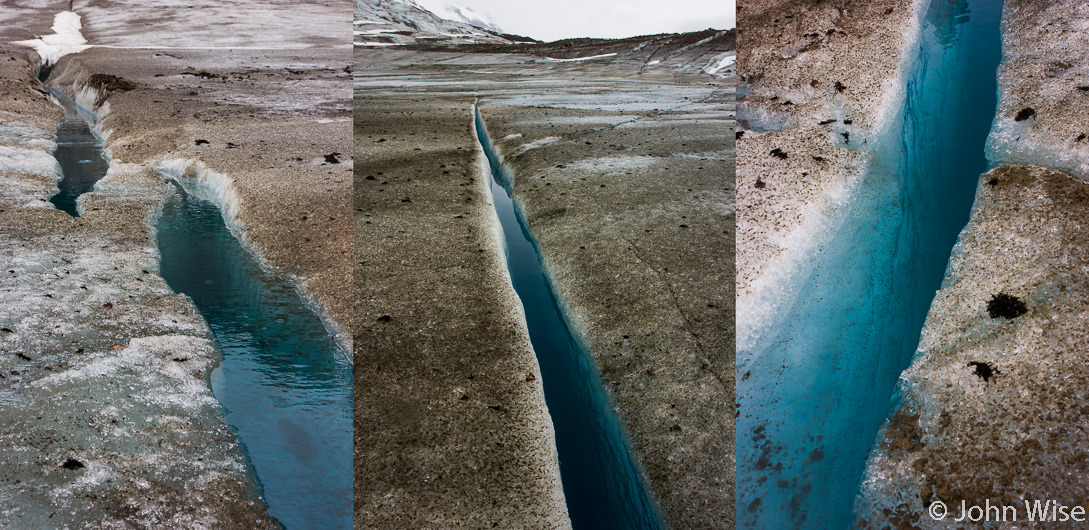

I know this is nothing more than rock, but how often in our urban lives do we see signs of a wild nature that used to be the earth we live on? I leave this here as my reminder that the details found in nature are not always easily explained, nor do they obey any laws of conformity or symmetry. I wonder how many of my fellow travelers took the time to see these details. From my observations, close to none.

This is the most beautiful flower ever discovered on the Alsek River in Alaska. It was surrounded by strawberry plants that, later in the season attest to its beauty by growing what must surely be the sweetest berries in all Alaska. The paw prints of a mighty large grizzly let us know that this patch belongs to a particular bear who must be awaiting its maturation; we choose not to wait for him.

The riot of color that bursts forth after viewing so much monochromatic landscape has been known to cause lasting damage to the eyesight of those not prepared for such an abrupt reintroduction to the palette of hues and tints that can be found in Alaskan wildflowers, such as with this example of Indian Paintbrush. A welder’s mask would do those folks well here.

Over the hill and out of the blooming fields, we catch our first look at Alsek Lake. I would have shown you greater breadth, but maybe you don’t have the experience of seeing the immensity of nature in one fell sighting. So try these bits of bergs mirrored in the stillness of the lake, admire the blue ice cube in the background, and be dazzled by the reflection of the mountain tops that are just out of sight.

The majority of our group has taken off. The doors to Alsek Lake cannot be seen from this perspective; another lookout with a better overview is required, and that is where they left to. In order to enter the lake, there are three “doors” that can be used. The first door is also known as “The Channel of Death.” You can enter through Door Number 1, but it’s not the best choice. Once taken, there is no way out besides getting through the lake. You risk encountering big icebergs, and if they block the way, well, there is no portaging over them. The next choice is Door Number 2, better but not ideal. The door you want to use is Door Number 3, but, and you knew there was a but, Door Number 3 is a shallow channel. Not only might it be too shallow to run, but on a previous Alsek trip for our boatman Bruce, the first two doors could not be taken, and Door Number 3 was still frozen over – portage time.

No, this is not a self-portrait, though I would like to have sat next to the iceberg-filled lake and grown like moss on a log. We agreed to meet the rest of the group back at the beach we stopped for lunch. Time to go.

We are passing through Door Number 3 on calm, shallow water. We admire the landscape while Bruce finds the deeper channels.

This is how shallow the water is, mere inches deep. It’s possible that in a day or two, or maybe in the previous days, this channel may have been high and dry; today, luck is on our side.

Here’s Shaun having successfully exited Door Number 3, which’s right behind him. In the bucket and mounted on the back of the raft is some sorry-wet wood that will be used for our fire should we not find sufficient supplies once we land.

As you can see surrounding our tents, there was plenty of driftwood in this camp. Moments after shooting this photo we heard a loud rumble in the lake but could not make out what rolled over. What we could see was a large wave radiating out and toward us. I was ready to head for the hills when we saw that the low-lying area of the lake in front of us diverted the wave left and right. All of a sudden, it became clear why there was so much driftwood on this shore – when really big stuff rolls over, the wave must be so large that it washes over this shore and deposits its collection of firewood here for easy access to the campers who call this home. Great, now how am I supposed to sleep knowing a lake tsunami could wash in overnight?