Heli-portage day. We were up early and rapidly pulling camp down while breakfast burritos were being prepared. After a quick meal, it was right back to packing and organizing all of our gear for today’s big portage. Dishes and cleaning the kitchen is a group effort as we have to be ready when our helicopter shows up. Tents are stored in empty food lockers, and the PFDs and paddles are lashed together in bundles. Food has been consolidated into the tightest pack possible, seeing we have consumed seven days of our provisions. Our sleeping bags are set to one side and our dry bags to another. The deflated rafts sit near shore. While most of us can help, it’s the boatmen who shoulder the majority of the work. The best we can do is to be efficient in getting our gear packed and moved to the staging area. Get to the unit early so we can pack up our shit because it’s going down the river too. After everything is staged for the final pack we start our wait for the pilot, who appeared about 30 minutes later.

Before our helicopter lands, we are briefed that NOTHING that could be blown away and caught up in the rotors should be loose. We are also informed that we will fly in three groups and that we should be attentive and listen to instructions. No silly exuberance is allowed. Get in the craft, buckle up, and help others do the same. Put on your headset. Do NOT slam the doors as they are expensive and relatively fragile; they are not car doors. Be aware of your situation: tail rotors chop, and turbines are hot and loud. We hear our transportation arriving just before we can spot it coming in low, and soon, he’s setting down and kicking up the dust. After our pilot Ian shuts down, he’s soon out and unloading the nets that will be slung under his helicopter and moved about seven miles downstream.

Before anyone heads down the river, we need all hands on deck to help move a serious amount of rafting gear and food onto the nets. There’s a limit to how much weight the helicopter can lift at one time and so it’s our boatmen’s job to use their best judgment to see that the weight gets distributed as evenly as possible across the three nets: one for each raft.

If any of the nets is too heavy, the pilot will put it back down after he weighs it, and we’ll have to repack that net. Our pilot, by now has already assessed the weather downstream and is busy determining how he wants to move us and our gear.

The net should be as evenly weighted as we can muster and everything in it should be solid to not shift when it’s dangling under the helicopter. Should anything alert the pilot that something isn’t safe, he will drop our gear in an instant to preserve life and maintain safety.

While it took us seven days to get to the Tweedsmuir Glacier, it only took our pilot 45 minutes from Haines Junction in Canada. Our gear was finished being loaded into the slings in less than 30 minutes. Time for another safety briefing, this time from our pilot, Ian. He explains how he expects us to board and exit the craft. He shows us how our seat belts work, where the emergency equipment and sat phone are along with a beacon, and where storage is for the personal bag we’ll be carrying. With that, the first five are boarding and will soon be airborne.

There they go, flying out over Turnback Canyon and the Tweedsmuir Glacier to some point downstream, where they will await the others and our gear. It was probably about 10 minutes down and 10 minutes back, based on when Ian returned to pick up the next group to be dropped off where the others were hanging out. Then, 20 minutes later, the helicopter returned to start moving our gear.

Only four of us were left in camp with these three slings of our gear about to be two slings. Bruce was directing operations this morning, and with Ian hovering over him and the river, he grabbed the hook and attached it to the sling.

One thousand two hundred and fifty pounds of gear is what the first load came in at.

The next sling weighed in at 1,360 pounds and the third at 1,280 pounds. All told, we are traveling with 3,890 pounds of gear, which, in just a few more minutes, will all be somewhere downstream. It’s strangely quiet here at our nearly deserted camp: just the four of us, a river, and some clouds – kind of empty feeling. Over in the mud, I spot a human footprint, one of the few remaining impressions that people had been here.

Now it’s our turn to lift off in this helicopter for our portage downriver, passing over this dangerous part of the river that has earned the nickname Turnback Canyon.

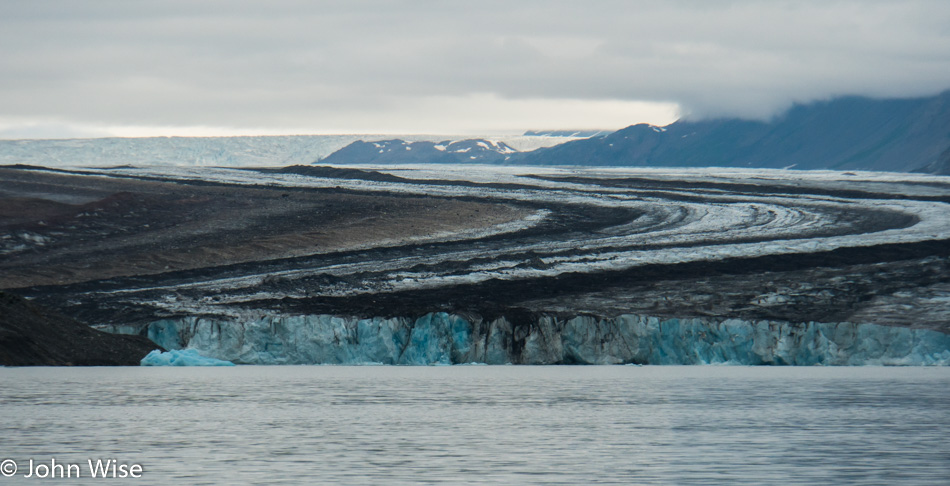

While the flight is only about 10 minutes long, the amount of visual stimulation and changing scenery is monumental, from the top of the Tweedsmuir Glacier on one side to the raging Alsek River below us.

Each turn and every angle offers more than the mind can comprehend and inventory.

The waters below us are falling rapidly through incredibly narrow chutes. How all of this water fits in this canyon is mind-boggling.

Taking these photos while flying over Turnback and the Tweedsmuir may feel obligatory, but doing so is a powerful distraction that is pulling me out of being fully in the moment. Instead of committing it all to memory, I’m capturing the impressions with a camera that will require me to view much of the experience on a computer.

My recommendation to others making this portage is to skip the photos or ask the one person who is best equipped and is going to take photos or make a video to share with the group so the majority can enjoy this rare moment flying low over a remote glacier and this treacherous canyon.

The landscape is bewildering, and while it is monumental from the river it becomes infinite when in the sky.

From up here, you realize just how tiny we are and how, down in that forest, a bear could be just a couple hundred feet away from you, and neither you nor it will know the other even existed.

In some way, we are like one of the trillions of water molecules being jettisoned out of that waterfall where the arch from the top to joining the river is the length of our life, and after it makes contact with the larger body of water, it will be lost in the flow, just as we will be in the flow of time.

The helicopter offers us many different views of our environment, and because of the speed we are traveling, mixed with our overcast sky, it’s a chore to try to grab worthwhile images of the world around us. I hope that this long photo essay will help convey a fraction of the complexity we were flying over.

We are nearly finished passing the Tweedsmuir Glacier, which means that somewhere out there along that river, we are going to be setting down and returning to our travels via raft.

One last look over the Tweedsmuir and its fog-covered ice fields. If only we could set down out there for a short while and explore the glacier. Then again, this is a pricey affair at $30 a minute. We’ll eat up approximately 285 air minutes of this helicopter’s time, with the entire cost of the portage costing roughly $9,000. So when you are left wondering why a trip in the remote wilds of the Yukon and Alaska can get pricey, you can start considering the cost of food being transported, people being delivered safely on both ends of the journey, and that your three or four guides must also earn a little something for being knowledgeable mentors, cooks, medics, and boatmen who work against some difficult conditions to show us these remote parts of the world.

Out there on one of the gravel islands are three rafts and ten others waiting for our arrival.

Some of the many details are nearly impossible to see when sitting inches over the river.

One last look back upriver to see where we just came from. If you glance near the bottom left of this photo, you can see some boiling water near the corner, which is not a rapid; it is water coming up from below the glacier.

There’s our group, and it appears they are almost ready to get going.

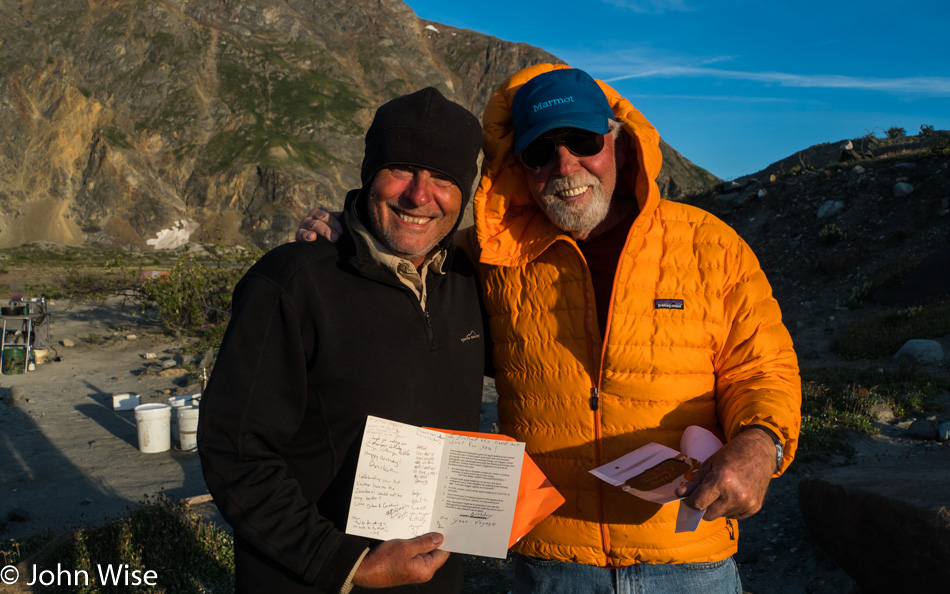

Our boatmen had a few things to send back with our pilot, and after a heartfelt thank you for delivering all of us downriver, he was about to take off again.

Time for our pilot, Ian, to make the hour-long flight back to Haines Junction in the Yukon, Canada. Our encounter with the outside world is done and we need to focus on continuing our journey down the Alsek.

Within 10 minutes of our landing, we were back on the river and were already looking for a pullout to make lunch.

On this side of the Tweedsmuir Glacier, we are starting to see the first signs of the rainforest, with birch, fir, and spruce being seen. We are also now on the most heavily braided part of this adventure as the river widens from this point forward.

Smoked salmon by the pound with bagels, red onions, fresh avocado, tomato, capers, cream cheese, and cookies. This is lunch slough style, meaning we paddled up a slough and away from the roar of the mighty Alsek. For the first time in a week, we are in near silence.

The dream journey through this river corridor would see me on a private trip taking an entire summer where we’d move like the glaciers, lingering in every spot and leaving the river at every opportunity to photo document the area. Instead, I have my camera at the ready at every opportunity and try to grab a decent image of the incredible scenery, but I can assure you that if the sun were out this would be an entirely different place. As I write this, I can’t help but think I’ve shared this sentiment before, maybe even on the last Alsek trip.

While there have been plenty of photos from our portage, our day is not over, and we have a few river miles to go before we stop to set up our next camp. If I didn’t mention it before, this is Thirsty, one of our boatmen.

I added this photo to this entry reluctantly as in low resolution, you miss much of the jagged nature of the rocks, but maybe you can imagine them or maybe one day I’ll be able to link the full-resolution images I shot. Also, you can notice how dramatically the light has changed between this image and the waterfall just above that was taken 40 minutes earlier.

I love these inflatable cruise ship hood ornaments, better known as firewood bundles, that we strap to our rafts so we may indulge in the luxury of a campfire late in the day.

This dead tree in the river gives you a good indication of just how shallow some of the braids are and how important it is for a boatman to choose the right channel. While the river is shallow here, you still don’t want to have to step in to help dislodge a raft with 2,000 pounds of gear and passengers as you cannot see what’s just below the surface and getting a foot snagged on a hidden branch or rock can be a serious threat.

Along the way, we passed the Vern-Mitchell Glacier, which I failed to get a reasonable photo of, and are now entering the Noisy Range. It was here in the appropriately named range that five years ago, we first heard and then saw a landslide in these mountains that has earned them their name.

About to pull ashore for camp as we drift along this sandy cut bank on the Alsek River.

Sun, clouds, water, trees, mountains, sun, snow, and ice all come together like the confluence of the Tatshenshini and Alsek Rivers here, where we are making camp for our eighth night sleeping in the wilderness. While the last hour on the river was tough due to falling into a salmon-induced coma (not just me, by the way), we set up camp pretty quickly.

With our tent set up and our gear stowed, we can get on with the other camp stuff, such as knitting and writing.

Caroline Wise is the first woman in history to be photographed knitting near the confluence of the Tatshenshini and Alsek Rivers. The Guinness committee didn’t seem all that impressed; then again, the socks she’s making are for me and not them.

Our previous trip here was during June, and the month and five years between these journeys make quite the difference. With such a short spring, summer, and fall jammed into about three months, June was lush compared to July, as things were brighter green back then. Many of the plants are dryer here at the end of July, with mushrooms nearly gone and the moss crispy and pulling back.

I was distracted from writing and instead took the opportunity, with our momentary burst of sunlight, to grab some photos of the beautiful plant life in camp.

Can there ever be enough glowing dryas pictured here?

It’s amazing to think that this is about seven weeks of growth, and much of it has started bolting to seed. In little more than a month, it will be winter here again, and we humans, along with these flowers, will be gone until next year when May brings the sun back, and by early June, this river corridor will jump back to life.

The sun poked its face into ours for a few minutes, and as quickly as it disappeared, the temperature started to drop with its departure. Our dinner tonight was cooked over some of that wood we collected earlier; we had barbecued ribeye steaks, cheesy potatoes, and cabbage salad, followed by a freshly baked Dutch oven coffee cake for dessert. Not an hour after dinner, most everyone retired to their tents while Pauly, Caroline, Keith, and I burned the midnight oil, chatting around the fire. In the photo are Steve “Sarge” Alt and William Mather.