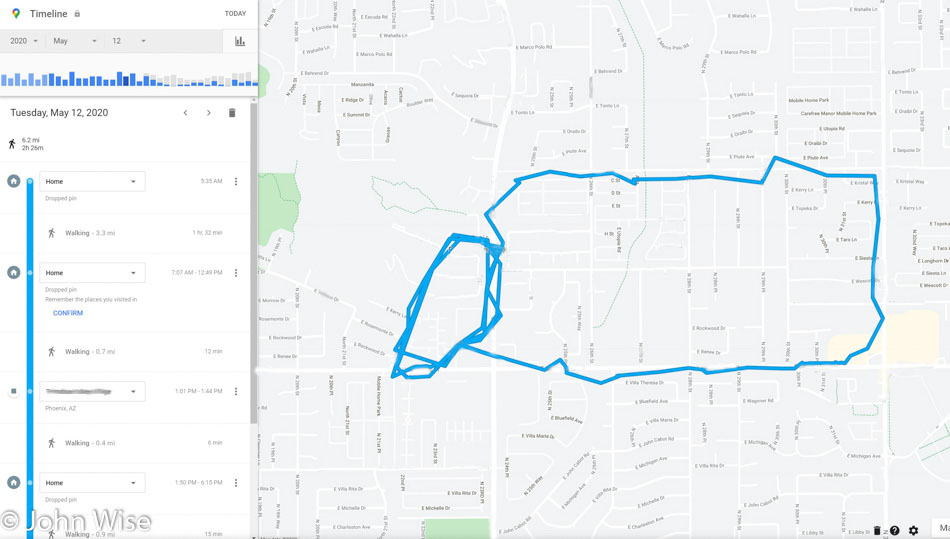

For 83 days, I’ve pretty much stayed within 3 miles of home, and over one 8-day period, I didn’t venture more than a mile from home. What I’m learning about this decreased mobility is that my imagination is starting to have profoundly quiet moments where I’m not feeling very motivated to delve into thinking. I’m beginning to wonder what the impact of experiencing the larger world outside of the overly familiar is for feeding my creativity. This then triggers the question: how do poverty and not having the means to explore further than your own neighborhood impact our critical and creative minds? Or, how does illness that limits mobility negatively impact our recovery and mental health?

I guess this is what others call boredom. Seriously, privileged me can honestly say I’ve not been bored in decades, but after this extended need to remove myself from the public, I’m starting to suffer the effects of not changing up my routine and getting out to gather new experiences. I can appreciate that there was enough momentum in my life that it’s taken me this long until these hints of boredom have started making themselves known, and I can’t say I want to be too quick to put it behind me. With all experiences, there are lessons to be discovered, and while there are fleeting moments of urgency to stem this creeping unease, I also feel obliged to see where it goes.

If my brain continues to draw blanks and I fail to find inspiration or motivation, does this defeat that part of my optimism that propels me to want to grasp in all directions? Hmm, this starts to sound like depression on the horizon, and that’s no Bueno.

Well, enough was enough, and so I ventured out. Went as far as Mekong Plaza nearly 30 miles away. I took my notebook along with the idea that if I found a relatively secluded place, I might try sitting down to work on this blog entry, but instead found the place crowded and experiencing a minor bout of agoraphobia. So, I grabbed a few things in the market, which was a challenge, too, due to how many people were shopping, and then headed over to In-N-Out Burger for some junk food therapy before going home. All of a sudden, home isn’t so boring, well maybe it is, but at least I’m happy to be back.

Back to this idea about mobility and the brain. I’d posit that when we move away from the familiar, inspiration strikes. If you are growing up in the inner city and your life is school and home, going to a club awakens your dreams. If you are in the countryside and visit a city, your perspective may be so shifted that upon returning home, your rural existence will have lost some of its charm. On the other hand, if you discover drugs and alcohol along the way, you could become lost in the numbness of complacency as you opt to stay home or at the bar, where your routine is dulled by the fog of inebriation.

So it would seem that if the stars align just right and you have access to a requisite amount of disposable income, along with the wherewithal to push yourself into new experiences, you may find yourself craving the novelty and making efforts to ensure you can continue to discover the part of life that inspires people to accomplish something extraordinary. But why is this the way I think it is? We are pattern recognition machines meant to wander through life trying to understand how things work, but when on a treadmill of a simple routine existence without much variation, our humanity is dulled, and we become addicted to our habits. In that addiction, we grow intolerant of those threatening to move us out of our comfort zone.

We have to move, we have to go places, and when we do, our mind goes with us and then wants more. But there’s a danger with this idea, as much of our culture is based on repetition that brings society to complacency. We are conditioned to watch the same sports, the same themes in movies, iterations on a theme regarding television and music, and frequent visits to our favorite restaurants. These habits are the filler for those times when we can’t go out to the lake, to France, or up the mountain. When we fully embrace our intellectual and physical mobility, strange things occur in us humans, our tolerance expands, our desire to try new things grows, and our need to seek out others who are also on a path of discovery becomes more important.

I’d venture to say that I want to believe that this is part of the spark of life, meaning we have an inherent need to get out. If we reach that station in life in which age or illness hamper our desire, we start to move towards giving up the ghost. If we are excited by what tomorrow might bring, a kind of zest drives us into that day, but if we dread the misery it could bring, we kill a little bit of ourselves.

This isn’t good enough to recognize this possible situation, what could a solution be? Obviously, we cannot all get on a plane and head into the many corners of the earth, nor can we all simultaneously set up camp in the national parks and hope to have a pleasant experience if we are surrounded by 1oos of thousands of people. We can sign up for a cooking class, try a new restaurant, go to a concert by a band from outside our country, join a book reading club, visit a guild to learn a craft or commit to doing any number of many things we’ve never done. Maybe there should be a self-help book for adding novelty to our lives on a regular basis. A one-year plan where the reader must choose from multiple choices of the things they’ll seek out over the course of the year and then commit to experiencing it.