I wonder how many people might read my blog and wonder what I was going to get out of going to Chiapas for a fiber arts tour with my wife. I’m getting a lot more than one might imagine, as the immersion in culture and awareness are off my chart. Secondly, witnessing the changing role of women and how the international interest in traditional fiber arts is empowering them is incredibly inspiring. Then in no particular order, I’m enjoying the food of Mexico that is not what we call Mexican food in the United States. Next, but in no way last, the whirlwind of activity is creating thousands, if not millions, of impressions that will forever repaint the canvas of any ideas I might have had of Mexico prior to this visit. One thing is certain: Mexico is not its border towns or the impressions held north of this country.

Our host Norma and my wife Caroline at the gift shop and cafe side of Museo Na Bolom, a.k.a., Casa del Jaguar. Our first stop of the day.

This was the home of Frans Blom and Gertrude “Trudi” Duby Blom here in San Cristóbal de las Casas. Frans was an archeologist, and his wife was a documentary photographer, journalist, anti-fascist activist, and environmental pioneer. Although they were Europeans (Frans from Denmark and Trudi from Switzerland), they shared a passion for the history and culture of the Maya in Chiapas and first met in the jungle of Chiapas in 1943, visiting the Lacandones. They bought this beautiful colonial house in 1950 and named it Casa Na Bolom. They used it as a base camp for expeditions, hosting visitors, exhibiting artifacts, and later on, growing trees to replenish the forests. Today, the spacious grounds and buildings not only house a museum but also a library, gardens, photography archive, cafe, and a number of rooms that can be rented. Frans passed away in 1963, and Trudi continued their work until her own passing in 1993.

Today, the museum is operated by a foundation that is supposed to carry the work forward of this husband-and-wife team whose ambition was to protect the Lacandon Maya and the rainforest of Chiapas.

Before cotton or wool can be used for weaving, they must first be carded, then spun, and then used to dress the backstrap loom.

Descendants of the original Maya people, the Lacandon were “discovered” by Frans Blom back in 1948. In this photo are respected elders of the Naha community Mateo Viejo on the left and Chan K’in Viejo on the right. Both men lived into their 90s. If you are curious about what happened to Mateo, he fell into boiling water as a child. Trudi, in particular, was awed by the Lacandon people, and Chan K’in became a good friend.

The ubiquitous backstrap loom found all over the region and the primary reason we are here.

A fragment of the Lacandon women’s traditional dress and a rattle. A few days ago, I photographed a fragment of a similar dress in the exact same style, but down below, I’ll be sharing a full image of this dress made of bark.

Tobacco is a spiritual tool and item for celebrations.

The man in sunglasses is our guide through a few of the rooms of the museum, I believe he’s related to Danny Trejo.

We never actually visited this room, nor were we told the story behind the textiles hanging here. They remain mystery clothes.

Vessels for burning copal, a resin popular with the Maya.

While I can say the obvious that this is a vessel, I cannot offer anything else about it. Maybe your visit to Na Bolom can fill in some of these details I’m glossing over.

Items found in a tomb. There’s a small black-and-white photo in the background on the left showing how things looked before their removal.

Skulls found in a cave covered with heavy mineral deposits.

A beautiful serving plate, details of which escape both of us.

Images of Maya royalty, likely a king or something similar carved into rings because, back in the day, this was the easiest way to see your leader.

Trudi Duby Blom wore this dress when accepting an award for something or another. Isn’t that a horrible way to write about someone’s life? Well, try as I might to find the information about what she won an award or recognition for, I can’t find it. So how do I know she won something? It was in the documentary we watched at the museum. We saw a Swedish king holding a speech in her honor, but do you think I took notes? Heck no, we can find everything on the internet until we can’t. This is a shame because it sure sounds as if Trudi’s life would be movie-worthy. She was arrested by Nazis, escaped WW2 Europe to Mexico, hung out with Frida Kahlo and other intellectuals in Mexico City, photographed and wrote about female Zapatista soldiers, all before meeting and falling in love with Frans.

Moving through the courtyard, I photographed above, I passed these three who allowed me to snap a photo; not sure if the baby agreed or not. We are on our way to the rear of the complex.

What a beautiful facility that would have been an exceptional home.

A special room, not always visited by tourists, but we were able to have a peek as special guests.

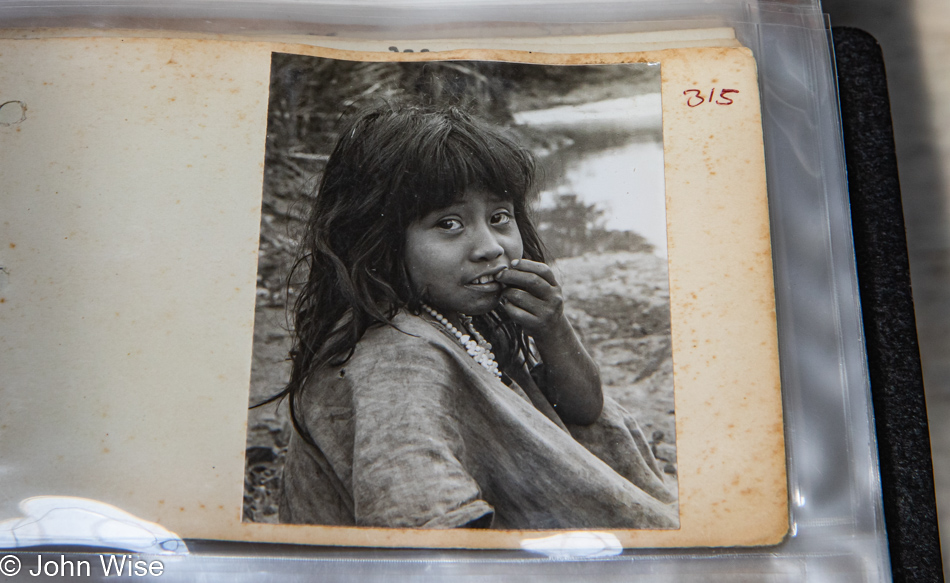

Gertrude Duby took nearly 55,000 photos during her time in Mexico, offering the world an incredible look into the indigenous people of Chiapas before the penetrating cultural intrusion that arrived with television and tourism. We found out that there is an ongoing effort to digitize and archive the originals, and one can buy prints.

While the others were checking out the photos of Gertrude, I wandered through the garden, and out in a small old hut was this Mayan shrine.

This was the formal dining room of Gertrude and Frans, with plenty of room for more than a few guests. While impossible to really see in this photo, there’s a Picasso over the window towards the top right of the photo. Just outside this room is a cafe where we were served traditional hot chocolate with some fresh sweet rolls. I didn’t include that photo as, to be honest, it was too sweet and couldn’t hold up to the cup of exquisite hot chocolate we enjoyed later this day at Cacao Nativa.

Not only is this space a museum and cafe, but there are also rooms to rent to travelers, a restaurant, and a library.

And finally, a small chapel for those not looking for the Mayan shrine found above.

Roads, streets, and paths are the indicators here that we are on the move to another destination.

Over the course of time that we’ll spend in the Chiapas region, I’ll likely post dozens of images of textiles, but I need to remind myself that I should include some of the scenes of what things looked like traveling between one place and the other.

If you see many similarities between these streets, well, I’ll walk the streets of Europe and never tire of the changing scenery, so I keep taking more photos here as the diversity is gorgeous to my senses. This can also be said about our many visits to the Grand Canyon, where the view can remain relatively static as this giant canyon stretched out before us, but that hasn’t stopped us from returning, again and again, to see it yet one more time.

So, welcome to my Mexican version of Champs-Élysées, where the streets of the historic center of San Cristóbal are as enchanting as anywhere else I’ve ever been.

Drive-by photography is not the optimal way to document things, but it works.

At one corner of a church and former convent stands this tower I found attractive and, for some reason, out of place. The old convent is now the Museo del Ámbar or Museum of Amber, while the Catholic church still functions in that capacity; it is called Iglesia Justo Juez. A little later today, we’ll visit the church, but will be too late to visit the museum, something else to come back to should we ever be able to return to this corner of Mexico.

We still have a ways to go but not too far.

At the edge of San Cristóbal, we are paying a visit to Jolom Mayaetik, a women’s art cooperative. As for the name Jolom Mayaetik, it means “Women who weave” in Tzotzil, with the coop representing women across the Chiapas Highlands, a.k.a. Los Altos de Chiapas. For about the first hour of our visit, we learned about the program, fundraising, building this facility, and cultural changes that, while taking longer than hoped for, they are seeing progress.

Magdalena López López, a master weaver from a small village near San Andrés Larráinzar is the person who wove this incredibly astonishing work. It seems near-incomprehensible that someone dared create something that would take the average person addicted to modern-age distractions directly into madness.

The San Francisco airport back in 2017 featured an exhibit in cooperation with Jolom Mayaetik, and the centerpiece was this extraordinary seven or 8-meter-long backstrap woven sampler that featured as many motifs as Magdalena López López could collect.

As the piece is rolled out, if you have some understanding of how backstrap weaving is done, this over 20-foot-long textile demands respect and will put you in awe.

When you come to understand that each thread added to this requires over two minutes and that each line ranges from 1 color to maybe a dozen before that weft (the horizontal lines) has been woven onto the warp (the vertical lines) to complete that line, you can see how a single line of thread can take up to approximately 20 minutes to complete. On average, a textile is about 14 threads per centimeter or 35 threads per inch. Click here to watch Magdalena practice her craft.

Now do the math: 7 meters or 23 feet would require nearly 10,000 horizontal threads. If the average row needed 10 minutes of weaving, we’d be looking at about 1,700 hours of work, but nobody could do this type of intense design for eight straight hours per day. Maybe you have begun to understand how undervalued these handcrafted pieces of textiles are. Ask yourself, if you were earning $10 per hour to create something like this, how many people do you know that would pay you approximately $20,000 to adequately compensate you for your effort, and this doesn’t take into account the learning and mastery that had to be acquired in the first place. So, in my view, we are looking at a textile worth between $100,000 and $140,000.

Now look back up at the images I’ve included and try to recognize that you are not just looking at pretty patterns that happened by chance; you are looking at history, life, culture, religious symbolism, the cosmos, farming, animals, and processes that are not part of our routine. That knowledge is shared from the minds of the Mayan women who have this incredible repository of ancestral wisdom that flows out of the past and into our eyes; in this sense, we are looking at the work of craftspeople offering us a kind of magic.

Nothing of this gravity was lost on Caroline, whose eyes were not able to belie the fact that the flow of women’s knowledge was moving through her and dragging the essence of that out of her and weaving her into the work of Magdalena López López and all the women who preceded her.

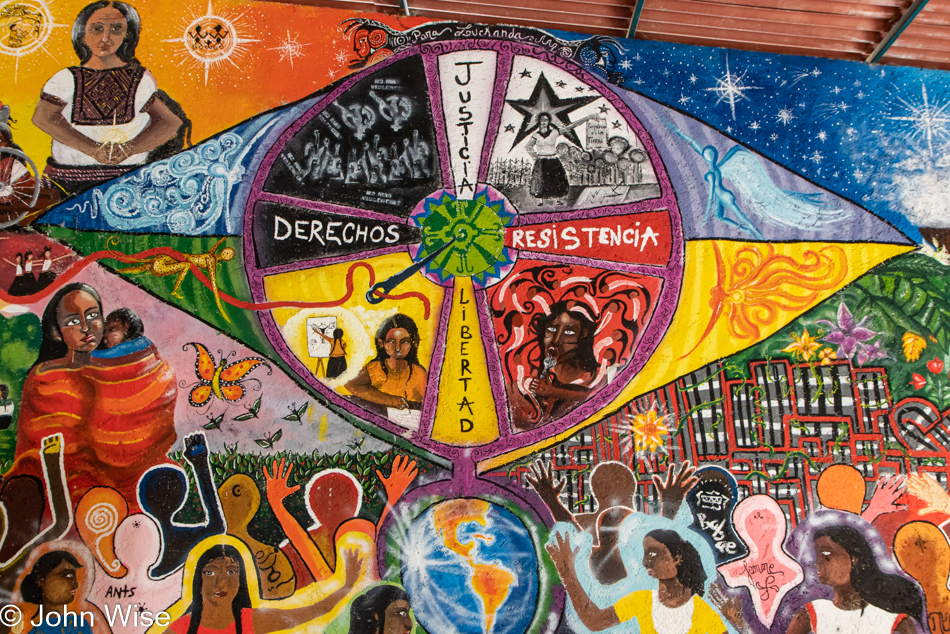

Justice, resistance, liberty, and rights are being drawn from everything in life on the thread that connects all into the center, a balance of things where women hope to find equality with all of their fellow humans, not just other women.

The sign says, “Indigenous women against violence!”

No visit is complete without making offerings in the form of cash transactions.

So many choices and so many days left demand that we pace ourselves on buying everything.

Norma’s been carrying one of these bags every day and has been extolling its value, comfort, and durability…it was inevitable that Caroline would have to have one. Add to the equation that Caroline was certain that these are created with the same or similar process that she practices at home in Arizona called sprang, which is a twisting/braiding method for creating materials with a lot of stretching ability.

The plan is not to return to the hotel but to stop on the way there to have a late lunch. Our driver cannot wait around, so those who want to eat here will have to walk back, needing about 15 minutes, or take a taxi.

Our lunch stop at Kokono restaurant. Owner and chef Claudia Sántiz has been recognized by Forbes magazine as one of the 50 most influential chefs in Mexico.

I told you that we’d make it back here to the Iglesia Justo Juez.

Never entered a church I didn’t like, though I should admit I’m not inclined to enter America’s churches housed in strip malls where a secondhand store once was, and now bunches of folding chairs are set up in front of the area where used old shoes once stood.

Yep, more streets.

But don’t think that was the end of the day with us walking into the sunset; we have an appointment down the road with an 81-year-old humanitarian. Tomorrow, he’ll be 82, but we’re not visiting him for his birthday; we’re visiting to learn about his work.

Maybe you are picking up on the idea that I’m enchanted with the lighting here on the late-day streets of San Cris?

If the fence were just a little bit straighter, I’d be convinced that these were two different stacked photos. The building in the background is the Cathedral de San Cristóbal de las Casas that’s been closed for five years due to the 2017 earthquake I mentioned earlier in my posts.

We’ve arrived at 38 Guadalupe Victoria with only the number 38 identifying where we are. In just a few minutes, we will begin a visit with Don Sergio Castro. First, he must finish by tending to a man with a wound, an indigenous man who is reluctant to visit a Mexican clinic, as the indigenous people of these lands know firsthand the bias against them. I should point out that the indigenous population is at a disadvantage in hospitals and clinics as they often speak only Tzotzil, Tzeltal, or Maya, all of which Don Sergio is fluent in.

The official name of this museum stop on our journey is Museo de Trajes Regionales de Sergio Castro. A great introduction to this man’s work is found in a short 5-minute video that we found seriously touching. You can watch it here.

While waiting for Don Sergio to finish treating the wound, we were welcomed into the room where our tour would begin.

The room is lined with the various traditional clothes of the people he tends to while out visiting villages in the nearby areas. Just yesterday we were in the village of Tenejapa, both of these huipiles are from that area.

The traditional clothing of San Juan Chamula, which we’ll be visiting in two days.

Had we been able to book the previous trip into the region with Norma, we would have been able to visit the Tenejapa carnival with that group, instead, we’ll have to be satisfied seeing this example of carnival dress.

While we are seeing a lot of pieces of clothing from the Pantelho people, we’ll not be visiting their village.

Somehow, I almost missed this detail Caroline asked me to focus on: the backstrap looms hanging behind the display of clothes.

Hey Caroline, what ethnic subgroup does this design represent? [I wish I knew! Some of the styles and motifs are becoming familiar by now, but I’m not sure about this one. Caroline]

Don Sergio has joined us by now and has been talking about the area where the various indigenous people hail from, what language they use, and the clothes used by men and women. In this photo, we see the man’s outfit on the left and the woman’s hammered bark outfit on the right, these are the traditional clothes of the Lacandon area who still speak Maya. The Lacandon are some of the people that would be considered the closest to the ancient ways of long ago. You might recognize the bark dress as similar to the one we saw in the textile museum a couple of days ago. As a reminder, the large circles represent the sun and moon, and the red dots are the stars.

Most days see Don Sergio traveling out of San Cris to one of the nearby communities to help people there with burns and open wounds that require some level of treatment so they don’t become life-threatening injuries. As he won’t accept payment, the grateful families gift him articles from their culture he can display in his museum. Then, from 4:00 to 7:00 p.m. daily he accepts walk-ins, tours begin after seeing his last patient.

We are ushered into a backroom for a slide presentation. Lucky for us, Don Sergio was able to acquire a new bulb for his ancient slide projector.

With the lights dimmed, the old familiar sound of the slide projector’s fan and mechanism for changing slides rattling along, we are treated to Don Sergio playing DJ too as he switched between cassettes featuring various sounds that accompany particular slides while he offers narration about what we’re seeing. In this instance, we are looking at the Monkey Men of Chamula. These are the ceremonial dancers of the carnival.

Why this is the Tutti-Frutti section of the museum remains a mystery to us. You should consider yourself lucky to be looking at all the tchotchkes because behind me on the wall are a couple of images that each feature about 15 images of people he’s treated, some of whom had suffered major burns that were horrific to see. Burns are common in the villages since cooking mainly happens with open fires.

This is the area where indigenous patients are able to find some care for burns and ailments that Don Sergio is able to offer assistance for and for free! When a medical situation doesn’t allow for help here at the clinic, he pays for the taxi to bring the person to a hospital with him, accompanying the family to help pave the way for a better experience for the reluctant patient.

Don Sergio Castro with Caroline Wise after we were able to make a nice donation to this man’s work of helping heal others. I should point out that he never charges a patient, ever. Sadly, the very large space he rents at a cost of about $12,000 pesos ($600) a month has some risks due to American and French appetites for property here in San Cristóbal de las Casas who’d pay a lot more for this sumptuous property. Fortunately, when this issue comes up, there are enough people in the region who demand he be allowed to stay. He’s not looking at being kicked out any time soon, but he can never know when the hammer of greed will strike him down and out.

Oh, how nice, a night market held in Plaza de la Paz which is the square in front of the cathedral. Adjacent to us at Plaza 31 de Marzo is the sound of live music where people are dancing. We’ll visit that soon enough, but we have something else on our agenda.

Here we are before dinner, having pre-dinner refreshments and hanging out with Gabriela (our translator and local guide) along with Ted and his wife Priscilla at Cacao Nativa. While I do love the sweet Belgian hot chocolate found at the Grand Canyon National Park, nothing really compares to this hot chocolate here in San Cristóbal. You are offered local cacao at strengths of 33%, 50%, 72%, 80%, and 100%; the last one we’ve heard is very bitter, even a bit sour. The classic way to drink this is with hot water, though they offer cow and almond milk as alternatives. The cup that is brought to you, while a little bit sweet, is definitely not the stuff sold north of the Mexican border. Just one sip, and we are sold on the need for these in the United States, though I think it would be a hard sale to Americans hooked on the caffeine flowing out of their coffee beans.

While we were sitting there chatting, a loud ruckus came up outside; it was a wedding procession with its own marching band.

With our minds blown regarding the amazing hot chocolate, the enchantment of watching the wedding party glide by, and appetites that were growing, we forgot all about going over to watch the band, even for a minute, and instead headed to Sarajevo Café Jardin on the recommendation of Gaby who was joining us.

She offered the most enthusiastic words espousing love for the ceviche de hongos or mushroom ceviche. While we’ve enjoyed our fair share of the popular cold seafood version of this that originates from Peru, there was something that sounded unappealing about the dish. Mind you, I love mushrooms, but cold raw mushrooms in lime juice weren’t striking my tastebud fantasies. OMFG was I wrong, a million times wrong. I didn’t need any of the other dishes we ordered; I could eat mushroom ceviche until mushrooms were growing out of my ears.

It’s apparent that this vacation is going to produce a sleep deficit, and although it’s late when we get into our hotel, and I can start tackling processing photos and taking notes if I’m lucky, we are in too early as outside our room we can hear the fireworks from what sounds like the Plaza 31 de Marzo. Do we throw our shoes back on and walk back up over the hill? No way, it’s going on 11:00 p.m., and our alarm is set for 6:00 a.m. We need our rest to face the million impressions we’ll gather tomorrow.

Lots of interesting and intriguing shots here, John. I look forward to reading the narrative that accompanies them.

Hello John Wise. Having just again exhibited the textiles of Jolom Mayaetik yesterday in SF and Berkeley, I’m happy to see your detailed report on your visit to the Jolom Mayaetik Centro de Capacitación on the outskirts of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas. Sounds like it was inspired by our exhibition of my collection of their work at the SFO art museum from September 2017 to spring 2018, with Magdalena López López’s magnificent tapestry muestra as its centerpiece.

During my initial trip to Chiapas in 2000, to see for myself Zapatista women overcoming two patriarchies, indigenous and Spanish/mestizo, I was so impressed the work and the spirit of the members of Jolom Mayaetik and K’inal Antsetik, I’ve volunteered to show and sell the cooperative’s textiles ever since.

If any of your readers are interested in seeing or buying Jolom Mayaetik textiles here in Berkeley, please pass on my email address. All proceeds go to the cooperative.